Roche limit

The Roche limit ( /ˈroʊʃ/), sometimes referred to as the Roche radius, is the distance within which a celestial body, held together only by its own gravity, will disintegrate due to a second celestial body's tidal forces exceeding the first body's gravitational self-attraction.[1] Inside the Roche limit, orbiting material will tend to disperse and form rings, while outside the limit, material will tend to coalesce. The term is named after Édouard Roche, the French astronomer who first calculated this theoretical limit in 1848.[2]

Contents |

Explanation

Typically, the Roche limit applies to a satellite disintegrating due to tidal forces induced by its primary, the body about which it orbits. Parts of the satellite that are closer to the primary are attracted by stronger gravity from the primary, whereas parts further away are repelled by stronger centrifugal force from the satellite's curved orbit. Some real satellites, both natural and artificial, can orbit within their Roche limits because they are held together by forces other than gravitation. Jupiter's moon Metis and Saturn's moon Pan are examples of such satellites, which hold together because of their tensile strength (that is, they are solid and not easily pulled apart). In extreme cases, objects resting on the surface of such a satellite could actually be lifted away by tidal forces. A weaker satellite, such as a comet, could be broken up when it passes within its Roche limit.

Since tidal forces overwhelm the gravity that might hold the satellite together within the Roche limit, no large satellite can gravitationally coalesce out of smaller particles within that limit. Indeed, almost all known planetary rings are located within their Roche limit, Saturn's E-Ring and Phoebe ring being notable exceptions. They could either be remnants from the planet's proto-planetary accretion disc that failed to coalesce into moonlets, or conversely have formed when a moon passed within its Roche limit and broke apart.

It is also worth considering that the Roche limit is not the only factor that causes comets to break apart. Splitting by thermal stress, internal gas pressure and rotational splitting are a more likely way for a comet to split under stress.

Determining the Roche limit

The limiting distance to which a satellite can approach without breaking up depends on the rigidity of the satellite. At one extreme, a completely rigid satellite will maintain its shape until tidal forces break it apart. At the other extreme, a highly fluid satellite gradually deforms leading to increased tidal forces, causing the satellite to elongate, further compounding the tidal forces and causing it to break apart more readily. Most real satellites would lie somewhere between these two extremes, with tensile strength rendering the satellite neither perfectly rigid nor perfectly fluid. The Roche limit is also usually calculated for the case of a circular orbit, although it is straightforward to modify the calculation to apply to the case (for example) of a body passing the primary on a parabolic or hyperbolic trajectory.

Rigid-satellite calculation

The rigid-body Roche limit is a simplified calculation for a spherical satellite, where the deformation of the body by tidal effects is neglected. The body is assumed to maintain its spherical shape while being held together only by its own self-gravity. Other effects are also neglected, such as tidal deformation of the primary, rotation and orbit of the satellite, and its irregular shape. These assumptions, although unrealistic, greatly simplify the Roche-limit calculation.

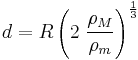

The Roche limit for a rigid spherical satellite excluding orbital effects, is the distance,  , from the primary at which the gravitational force on a test mass on the surface of the object is exactly equal to the tidal force pulling the object away from the object:[3]

, from the primary at which the gravitational force on a test mass on the surface of the object is exactly equal to the tidal force pulling the object away from the object:[3]

,

,

where  is the radius of the primary,

is the radius of the primary,  is the density of the primary, and

is the density of the primary, and  is the density of the satellite. Note that this does not depend on how large the orbiting object is, but only on the ratio of densities. This is the orbital distance inside of which loose material (e.g., regolith or loose rocks) on the surface of the satellite closest to the primary would be pulled away, and likewise material on the side opposite the primary will also be pulled away from, rather than toward, the satellite.

is the density of the satellite. Note that this does not depend on how large the orbiting object is, but only on the ratio of densities. This is the orbital distance inside of which loose material (e.g., regolith or loose rocks) on the surface of the satellite closest to the primary would be pulled away, and likewise material on the side opposite the primary will also be pulled away from, rather than toward, the satellite.

If the satellite is more than twice as dense as the primary, as can easily be the case for a rocky moon orbiting a gas giant, then the Roche limit will be inside the primary and hence not relevant.

Derivation of the formula

In order to determine the Roche limit, we consider a small mass  on the surface of the satellite closest to the primary. There are two forces on this mass

on the surface of the satellite closest to the primary. There are two forces on this mass  : the gravitational pull towards the satellite and the gravitational pull towards the primary. Assuming that the satellite is in free fall around the primary and that the tidal force is the only relevant term of the gravitational attraction of the primary. This assumption is a simplification as free-fall only truly applies to the planetary center, but will suffice for this derivation.[4]

: the gravitational pull towards the satellite and the gravitational pull towards the primary. Assuming that the satellite is in free fall around the primary and that the tidal force is the only relevant term of the gravitational attraction of the primary. This assumption is a simplification as free-fall only truly applies to the planetary center, but will suffice for this derivation.[4]

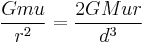

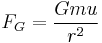

The gravitational pull  on the mass

on the mass  towards the satellite with mass

towards the satellite with mass  and radius

and radius  can be expressed according to Newton's law of gravitation.

can be expressed according to Newton's law of gravitation.

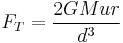

the tidal force  on the mass

on the mass  towards the primary with radius

towards the primary with radius  and mass

and mass  , at a distance

, at a distance  between the centers of the two bodies, can be expressed approximately as

between the centers of the two bodies, can be expressed approximately as

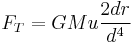

.

.

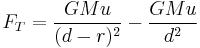

To obtain this approximation, find the difference in the primary's gravitational pull on the center of the satellite and on the edge of the satellite closest to the primary:

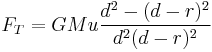

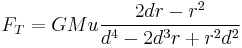

In the approximation where r<<R and R<d, we can say that the  in the numerator and every term with

in the numerator and every term with  in the denominator goes to zero, which gives us:

in the denominator goes to zero, which gives us:

The Roche limit is reached when the gravitational force and the tidal force balance each other out.

or

,

,

which gives the Roche limit,  , as

, as

.

.

However, we don't really want the radius of the satellite to appear in the expression for the limit, so we re-write this in terms of densities.

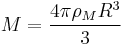

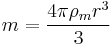

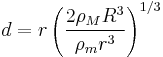

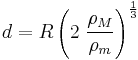

For a sphere the mass  can be written as

can be written as

where

where  is the radius of the primary.

is the radius of the primary.

And likewise

where

where  is the radius of the satellite.

is the radius of the satellite.

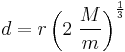

Substituting for the masses in the equation for the Roche limit, and cancelling out  gives

gives

,

,

which can be simplified to the Roche limit:

.

.

Fluid satellites

A more accurate approach for calculating the Roche Limit takes the deformation of the satellite into account. An extreme example would be a tidally locked liquid satellite orbiting a planet, where any force acting upon the satellite would deform it into a prolate spheroid.

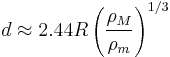

The calculation is complex and its result cannot be represented in an exact algebraic formula. Roche himself derived the following approximate solution for the Roche Limit:

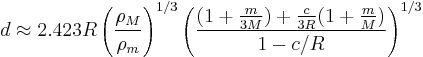

However, a better approximation that takes into account the primary's oblateness and the satellite's mass is:

where  is the oblateness of the primary. The numerical factor is calculated with the aid of a computer.

is the oblateness of the primary. The numerical factor is calculated with the aid of a computer.

The fluid solution is appropriate for bodies that are only loosely held together, such as a comet. For instance, comet Shoemaker–Levy 9's decaying orbit around Jupiter passed within its Roche limit in July 1992, causing it to fragment into a number of smaller pieces. On its next approach in 1994 the fragments crashed into the planet. Shoemaker–Levy 9 was first observed in 1993, but its orbit indicated that it had been captured by Jupiter a few decades prior. [1]

Derivation of the formula

As the fluid satellite case is more delicate than the rigid one, the satellite is described with some simplifying assumptions. First, assume the object consists of incompressible fluid that has constant density  and volume

and volume  that do not depend on external or internal forces.

that do not depend on external or internal forces.

Second, assume the satellite moves in a circular orbit and it remains in synchronous rotation. This means that the angular speed  at which it rotates around its center of mass is the same as the angular speed at which it moves around the overall system barycenter.

at which it rotates around its center of mass is the same as the angular speed at which it moves around the overall system barycenter.

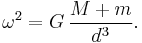

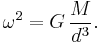

The angular speed  is given by Kepler's third law:

is given by Kepler's third law:

When M is very much bigger than m, this will be close to

The synchronous rotation implies that the liquid does not move and the problem can be regarded as a static one. Therefore, the viscosity and friction of the liquid in this model do not play a role, since these quantities would play a role only for a moving fluid.

Given these assumptions, the following forces should be taken into account:

- The force of gravitation due to the main body;

- the centrifugal force in the rotary reference system; and

- the self-gravitation field of the satellite.

Since all of these forces are conservative, they can be expressed by means of a potential. Moreover, the surface of the satellite is an equipotential one. Otherwise, the differences of potential would give rise to forces and movement of some parts of the liquid at the surface, which contradicts the static model assumption. Given the distance from the main body, our problem is to determine the form of the surface that satisfies the equipotential condition.

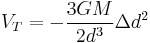

As the orbit has been assumed circular, the total gravitational force and centrifugal force acting on the main body cancel. Therefore, the force that affects the particles of the liquid is the tidal force, which depends on the position with respect to the center of mass, already considered in the rigid model. For small bodies, the distance of the liquid particles from the center of the body is small in relation to the distance d to the main body. Thus the tidal force can be linearized, resulting in the same formula for FT as given above. While this force in the rigid model depends only on the radius r of the satellite, in the fluid case we need to consider all the points on the surface and the tidal force depends on the distance Δd from the center of mass to a given particle projected on the line joining the satellite and the main body. We call Δd the radial distance. Since the tidal force is linear in Δd, the related potential is proportional to the square of the variable and for  we have

we have

We want to determine the shape of the satellite for which the sum of the self-gravitation potential and  is constant on the surface of the body. In general, such a problem is very difficult to solve, but in this particular case, it can be solved by a skillful guess due to the square dependence of the tidal potential on the radial distance Δd

is constant on the surface of the body. In general, such a problem is very difficult to solve, but in this particular case, it can be solved by a skillful guess due to the square dependence of the tidal potential on the radial distance Δd

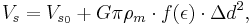

Since the potential VT changes only in one direction, i.e. the direction toward the main body, the satellite can be expected to take an axially symmetric form. More precisely, we may assume that it takes a form of a solid of revolution. The self-potential on the surface of such a solid of revolution can only depend on the radial distance to the center of mass. Indeed, the intersection of the satellite and a plane perpendicular to the line joining the bodies is a disc whose boundary by our assumptions is a circle of constant potential. Should the difference between the self-gravitation potential and VT be constant, both potentials must depend in the same way on Δd. In other words, the self-potential has to be proportional to the square of Δd. Then it can be shown that the equipotential solution is an ellipsoid of revolution. Given a constant density and volume the self-potential of such body depends only on the eccentricity ε of the ellipsoid:

where  is the constant self-potential on the intersection of the circular edge of the body and the central symmetry plane given by the equation Δd=0.

is the constant self-potential on the intersection of the circular edge of the body and the central symmetry plane given by the equation Δd=0.

The dimensionless function f is to be determined from the accurate solution for the potential of the ellipsoid

and, surprisingly enough, does not depend on the volume of the satellite.

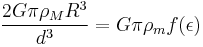

Although the explicit form of the function f looks complicated, it is clear that we may and do choose the value of ε so that the potential VT is equal to VS plus a constant independent of the variable Δd. By inspection, this occurs when

This equation can be solved numerically. The graph indicates that there are two solutions and thus the smaller one represents the stable equilibrium form (the ellipsoid with the smaller eccentricity). This solution determines the eccentricity of the tidal ellipsoid as a function of the distance to the main body. The derivative of the function f has a zero where the maximal eccentricity is attained. This corresponds to the Roche limit.

More precisely, the Roche limit is determined by the fact that the function f, which can be regarded as a nonlinear measure of the force squeezing the ellipsoid towards a spherical shape, is bounded so that there is an eccentricity at which this contracting force becomes maximal. Since the tidal force increases when the satellite approaches the main body, it is clear that there is a critical distance at which the ellipsoid is torn up.

The maximal eccentricity can be calculated numerically as the zero of the derivative of f'. One obtains

which corresponds to the ratio of the ellipsoid axes 1:1.95. Inserting this into the formula for the function f one can determine the minimal distance at which the ellipsoid exists. This is the Roche limit,

Roche limits for selected examples

The table below shows the mean density and the equatorial radius for selected objects in the Solar System.

| Primary | Density (kg/m³) | Radius (m) |

|---|---|---|

| Sun | 1,408 | 696,000,000 |

| Jupiter | 1,326 | 71,492,000 |

| Earth | 5,513 | 6,378,137 |

| Moon | 3,346 | 1,738,100 |

| Saturn | 687 | 60,268,000 |

| Uranus | 1,318 | 25,559,000 |

| Neptune | 1,638 | 24,764,000 |

Using these data, the Roche Limits for rigid and fluid bodies can easily be calculated. The average density of comets is taken to be around 500 kg/m³.

The table below gives the Roche limits expressed in metres and in primary radii. The true Roche Limit for a satellite depends on its density and rigidity.

| Body | Satellite | Roche limit (rigid) | Roche limit (fluid) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance (km) | R | Distance (km) | R | ||

| Earth | Moon | 9,496 | 1.49 | 18,261 | 2.86 |

| Earth | average Comet | 17,880 | 2.80 | 34,390 | 5.39 |

| Sun | Earth | 554,400 | 0.80 | 1,066,300 | 1.53 |

| Sun | Jupiter | 890,700 | 1.28 | 1,713,000 | 2.46 |

| Sun | Moon | 655,300 | 0.94 | 1,260,300 | 1.81 |

| Sun | average Comet | 1,234,000 | 1.78 | 2,374,000 | 3.42 |

If the primary is less than half as dense as the satellite, the rigid-body Roche Limit is less than the primary's radius, and the two bodies may collide before the Roche limit is reached.

How close are the solar system's moons to their Roche limits? The table below gives each inner satellite's orbital radius divided by its own Roche radius. Both rigid and fluid body calculations are given. Note Pan, Metis, and Naiad in particular, which may be quite close to their actual break-up points.

In practice, the densities of most of the inner satellites of giant planets are not known. In these cases, shown in italics, likely values have been assumed, but their actual Roche limit can vary from the value shown.

| Primary | Satellite | Orbital Radius / Roche limit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (rigid) | (fluid) | ||

| Sun | Mercury | 104:1 | 54:1 |

| Earth | Moon | 41:1 | 21:1 |

| Mars | Phobos | 172% | 89% |

| Deimos | 451% | 234% | |

| Jupiter | Metis | ~186% | ~94% |

| Adrastea | ~188% | ~95% | |

| Amalthea | 175% | 88% | |

| Thebe | 254% | 128% | |

| Saturn | Pan | 142% | 70% |

| Atlas | 156% | 78% | |

| Prometheus | 162% | 80% | |

| Pandora | 167% | 83% | |

| Epimetheus | 200% | 99% | |

| Janus | 195% | 97% | |

| Uranus | Cordelia | ~154% | ~79% |

| Ophelia | ~166% | ~86% | |

| Bianca | ~183% | ~94% | |

| Cressida | ~191% | ~98% | |

| Desdemona | ~194% | ~100% | |

| Juliet | ~199% | ~102% | |

| Neptune | Naiad | ~139% | ~72% |

| Thalassa | ~145% | ~75% | |

| Despina | ~152% | ~78% | |

| Galatea | 153% | 79% | |

| Larissa | ~218% | ~113% | |

| Pluto | Charon | 12.5:1 | 6.5:1 |

See also

- Roche lobe

- Chandrasekhar limit

- Hill sphere

- Spaghettification (a rather extreme tidal distortion)

- Black hole

- Triton (moon) (Neptune satellite)

- Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9

References

- ^ Eric W. Weisstein (2007). "Eric Weisstein's World of Physics - Roche Limit". scienceworld.wolfram.com. http://scienceworld.wolfram.com/physics/RocheLimit.html. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- ^ NASA. "What is the Roche limit?". NASA - JPL. http://www2.jpl.nasa.gov/saturn/faq.html#roche. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- ^ see calculation in Frank H. Shu, The Physical Universe: an Introduction to Astronomy, p. 431, University Science Books (1982), ISBN 0935702059.

- ^ Gu et al. "The effect of tidal inflation instability on the mass and dynamical evolution of extrasolar planets with ultrashort periods". Astrophysical Journal. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2003ApJ...588..509G. Retrieved May 1, 2003.

Other uses

- Roche Limit is the name of a Canadian Electronic pop band.

Sources

- Édouard Roche: "La figure d'une masse fluide soumise à l'attraction d'un point éloigné" (The figure of a fluid mass subjected to the attraction of a distant point), part 1, Académie des sciences de Montpellier: Mémoires de la section des sciences, Volume 1 (1849) 243–262. 2.44 is mentioned on page 258. (French)

- Édouard Roche: "La figure d'une masse fluide soumise à l'attraction d'un point éloigné", part 2, Académie des sciences de Montpellier: Mémoires de la section des sciences, Volume 1 (1850) 333–348. (French)

- Édouard Roche: "La figure d'une masse fluide soumise à l'attraction d'un point éloigné", part 3, Académie des sciences de Montpellier: Mémoires de la section des sciences, Volume 2 (1851) 21–32. (French)

- George Howard Darwin, "On the figure and stability of a liquid satellite", Scientific Papers, Volume 3 (1910) 436–524.

- James Hopwood Jeans, Problems of cosmogony and stellar dynamics, Chapter III: Ellipsoidal configurations of equilibrium, 1919.

- S. Chandrasekhar, Ellipsoidal figures of equilibrium (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1969), Chapter 8: The Roche ellipsoids (189–240).

- S. Chandrasekhar, "The equilibrium and the stability of the Roche ellipsoids", Astrophysical Journal 138 (1963) 1182–1213.

External links

- Discussion of the Roche Limit

- Audio: Cain/Gay - Astronomy Cast Tidal Forces Across the Universe - July 2007.

![f(\epsilon) = \frac{1 - \epsilon^2}{\epsilon^3} \cdot \left[ \left(3-\epsilon^2 \right) \cdot \mathrm{arsinh} \left(\frac{\epsilon}{\sqrt{1-\epsilon^2}} \right) -3 \epsilon \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/5937e45a709d58479a5d292b3277a2ed.png)

![d \approx 2{.}423 \cdot R \cdot \sqrt[3]{ \frac {\rho_M} {\rho_m} } \,.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/6283d36c2b8bc6cb6c268b9ea9fd89c3.png)